Drawdowns & Corrections

(This is the second post in a series reconciling stock price movements in the medium and long term. The first post explained stock price fluctuations using a mental model of Maxima and Minima.)

The long-term market movement is made up of a series of episodes, each with their local Minima and Maxima.

As markets rise, the investor’s portfolio keeps growing, peaking near the Maxima. A very interesting thing happens here. At the peak, the highest value reached by the portfolio becomes the baseline in the investor’s mind. Say, the investor started with Rs 20 Lacs and their highest portfolio value stands at Rs 60 Lacs. The investor’s mind is now anchored to this number. So much so, that if the portfolio were to drop to 40 Lacs, it feels like a real loss. The reality is that the investor is making returns of 100% (20 Lacs –> 40 Lacs), but that is not how our minds operate.

Even a paper loss feels significant. This quirk of the human mind is called the anchoring bias.

As the market falls from its peak Maxima, investors incur losses called Drawdowns Losses, or simply Drawdowns. The more the market falls from its Maxima, the more severe the drawdown. Drawdowns reach their maximum at the point of minima.

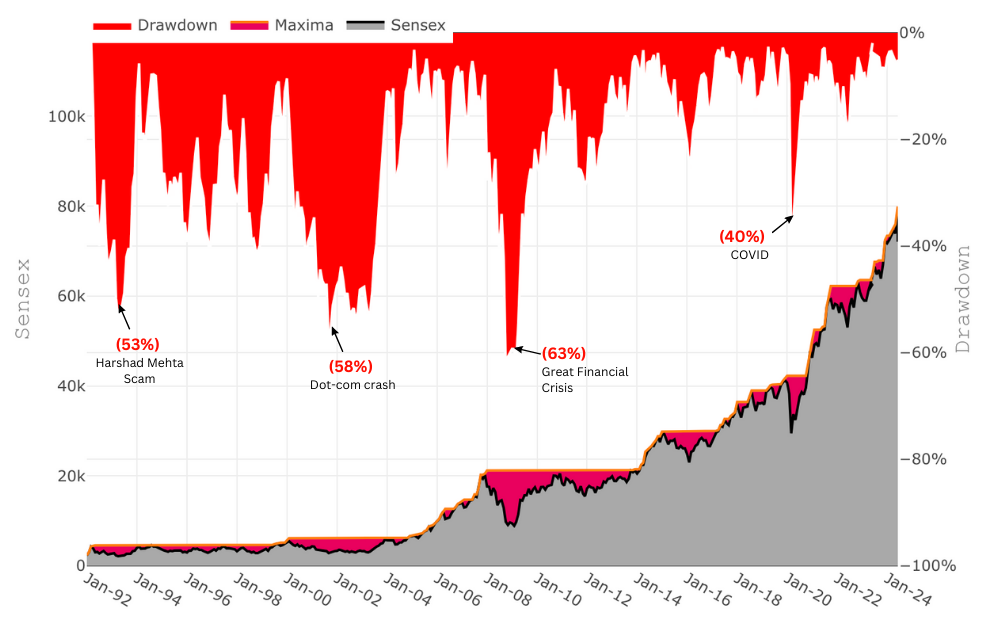

The chart below overlays the Sensex and its Maxima and Minima for the past 30 years. The drawdowns are shown coming from the top and measured as % loss.

During the 2008 financial crisis, the peak drawdown was 63%, meaning the average investor lost ~63% of their wealth compared to the previous maxima. The losses of the Harshad Mehta scam of 1992 and the Dot-com crash of 2001 were in their 50s, while the recent Covid crash was 40%.

History shows that markets can fall, and fall significantly.

(Those who are further interested to rewind the markets and replay the drawdown losses can try this app)

Selling in anticipation of market decline

Why can’t smart investors sell at the peak of the bull market and avoid losses? This would save them much distress and, furthermore, they can buy back their holdings at the market’s bottom.

There’s a small problem. As the bull market proceeds, the investor can’t predict the peak maxima. The peak is only known in hindsight.

If an investor were to sell their holdings, and the market kept rising, it would invoke the worst kind of regret. It’s very tough to watch the stocks you sold keep rising. Most investors who end up in this position throw in the towel at some point and end up re-purchasing the same stocks at higher prices to alleviate their regret.

Ben Graham relates the story of Isaac Newton in The Intelligent Investor,

And back in the spring of 1720, Sir Isaac Newton owned shares in the South Sea Company, the hottest stock in England. Sensing that the market was getting out of hand, Newton dumped his South Sea shares, pocketing a 100% profit totaling £7,000.

But just months later, swept up in the wild enthusiasm of the market, Newton jumped back in at a much higher price—and lost £20,000 (or more than $3 million in today’s money).

For the rest of his life, he forbade anyone to speak the words “South Sea” in his presence.

Assume that there were men more resolute than Newton, who could sell all their holdings and resisted buying at higher prices. Eventually, the market will fall and stock prices will drop below our investor’s sale price. The problem now is: when does the investor buy? Since the bottom of the correction is unknown, there’s no point at which one can purchase without facing immediate losses.

Also, buying entire positions while the market news is bad and stocks are falling is extremely complicated.

The investor is caught like a deer in the headlights, with no idea what to do. In the process, he has permanently traded his long-term holdings. Bill Ackman nicely summed it up in a recent letter to his investors,

We do not typically sell our core portfolio holdings even if we believe it is highly probable that they will decline in price in the short term, as long as our view of their long-term potential remains largely unchanged.

A short-term trading program might enable us to avoid a small loss at the much larger cost of missing substantial stock price increases thereafter. As a result, we do not trade around our long-term holdings..

One may not always agree with Ackman's actions, but he is spot on here.

Living through a drawdown

When faced with drawdowns, the best course of action for an investor is to do nothing. The least that an investor must do is not sell their holdings during a correction, no matter how deep.

From a maxima and minima standpoint, a down period is simply the time before the next higher move that investors have to endure. (It is true that some stocks may never recover, but we’re discussing the market).

In this light, drawdowns are a feature of markets, not a bug. Long-term investors are not expected to nullify these losses, but rather expected to take them on their chin.

Imagine that markets had no volatility, crashes, and drawdowns. Then all investors would readily invest in equities, as they invest in Fixed Deposits and Bonds, without the fear of any loss. Evidently, the returns on equities would mirror those of safer instruments.

High returns do not come free. Investors seeking them have to bear some risk. Drawdown losses are the price paid by long-term investors for earning large returns. This is just how the process of risk works.

Charlie Munger had this to say to investors,

If you're not willing to react with equanimity to a market price decline of 50% two or three times a century, you're not fit to be a common shareholder and you deserve the mediocre result you're going to get.

Market bottoms are great opportunities

As the market keeps falling, every piece of bad news is accounted for. Most investors who needed to sell have already done so. At this point, it takes only a small amount of positive news for a new upward trend to begin. Justin Mamis writes in The Nature of Risk,

The single best time to buy a stock – you can put this in your will for your grandchildren to rely on – is when, given bad news, the stock refuses to go down any more.

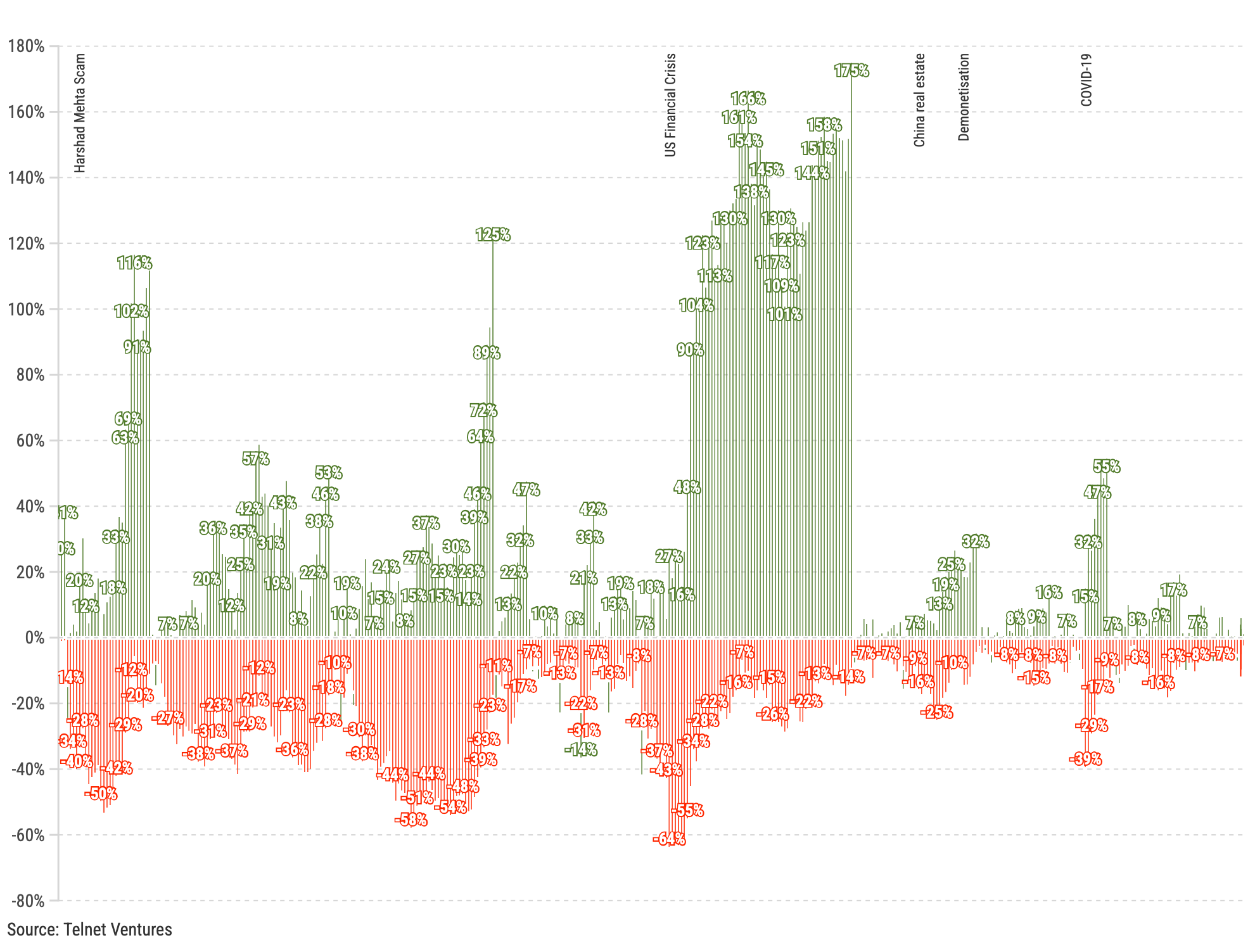

The below chart plots drawdown losses in red and the corresponding rise from the Minima in green, covering the past 30 years of the Sensex. As you can see, after every correction, the market consistently offers significant profits, although it takes some time.

Take the 2008 Global Financial Crisis, for example. The Sensex had a drawdown of over 60%. However, investors who bought at the bottom would have seen their investments appreciate by 100%-175% as the market recovered and reached new heights.

Bear markets offer long-term investors opportunities for significant gains at low risks. When fear peaks and the market absorbs negative sentiment, a powerful rebound is likely.

Stock market folks have a saying that "a stock that declines 50% must increase 100% to return to its original amount". Conversely, buying at the bottoms, when a stock is already down 50%, is the safest way to make 100% returns.

One important point to note is that investors who are buying in a bear market don’t have to time the market’s absolute bottom. Purchases made at any level will make returns after the crisis is over and the market starts moving upwards. Obviously, buying when the pain is highest will be more profitable than buying very early. (If it is gut-wrenching, it is a signal to buy).

However, buying during crises is easier said than done. With the investor’s psychology and survival instincts urging them to sell, it takes courage to step in and buy. One market guru commented that buying in crises "feels almost like death" while another said,

The very best stock purchases make you feel like throwing up.

Planning for future drawdowns

Drawdowns are the price of admission to equity markets. Trying to avoid these losses can lead to sub-optimal returns.

But is there really nothing that the smart investor can do to prepare themselves for the impending correction? Is it at least possible to soften the impact and ensure that we do not capitulate at the bottom of the market? And where does one get the cash to buy at the juicy valuations at the bottoms? These questions form the subject of the next post.

Go to part3: Positioning for the Next Market Phase

Member discussion